Excess cash is cash balance beyond what a business requires to fulfill its daily operational money needs. Usually, analysts consider 2% of the revenues of a company as the cash it really needs to function properly. Thus, the remaining cash is excess, but this is an assumption.

That’s the gist of it.

For a more comprehensive guide on what is excess cash in business, how to find excess cash, and why it impacts company valuations, keep reading:

Excess Cash Definition

Excess cash is cash above what a company needs in order to perform its daily operations.

Most companies hold more cash—in the form of deposits or marketable securities—than what they need for their operating requirements.

This surplus cash is a non-operating asset in the balance sheet. The problem?

When valuing a business, you want to focus on its operating components to get an accurate economic picture of the company’s performance.

Therefore, you should exclude everything that contributes to revenues (positively or negatively) but has nothing to do with the core business activity.

Take for example a marketing corporation that happens to earn 1% interest on its savings account. When valuing the corporation, you should exclude that income and the asset that generates it. Or at least treat them differently.

Now, what is considered excess cash?

Excess Cash Calculation

All companies need some liquidity to go about their business.

There’s no excess cash formula. Firms don’t disclose exactly how much cash they need to run their daily operations.

On top of that, it’s a value that is always changing. And it varies from industry to industry, and according to the size of the company.

For instance, early-stage companies need more capital available to fund growth opportunities, and as a result have higher working capital needs.

And companies in industries where a negative cash conversion cycle is common—meaning they receive cash flows from customers before having to pay suppliers—need less cash to run their daily operations compared to companies that give out a lot of credit to customers.

So you need to make an assumption according to the business you’re analyzing:

#1) Percentage of Revenue

This is the most common assumption.

Morgan Stanley suggests 2% of revenues as a rule of thumb for the cash a mature company needs to run its daily operations. The remaining cash and equivalents in the balance sheet are considered excess cash.

For less predictable companies with greater growth prospects, a ratio of cash to revenue up to five percent may be appropriate.

Morgan Stanley’s Counterpoint Global, October 2022

So for example, imagine a company that has $8M in cash and cash equivalents on its balance sheet, and $100M in revenues.

Following the 2% rule of thumb 100×0.02=$2M of its cash balance is working cash, while the remaining 8-2=$6M is excess cash holdings (and considered a non-operating asset).

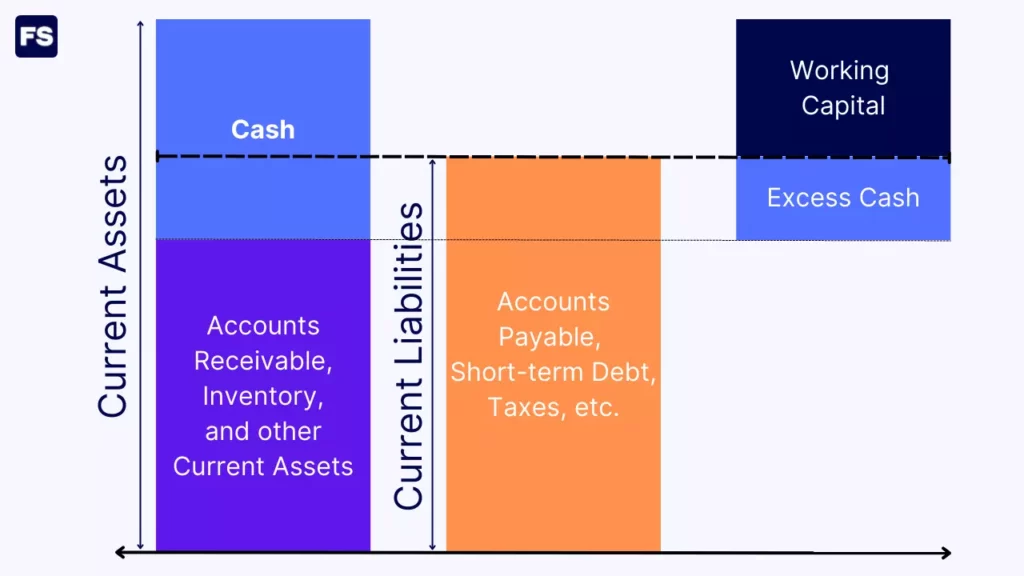

#2) Based on Working Capital

You can also start by calculating the net working capital (using the difference between total current assets and liabilities).

Then, if the difference is positive, check if the cash balance is bigger than the working capital itself.

The cash beyond the working capital is the excess cash.

The logic behind it is this:

When working capital is negative it is a source of funds. When it is positive it’s an application of funds.

Positive working capital means the business has enough resources to cover its short-term obligations.

The working capital number is how much of a buffer the business has after paying all immediate obligations.

If you remove the difference between cash balance and working capital, you can still cover short-term commitments, and still have a buffer.

That difference is excess cash.

Again, this only applies if the cash balance if higher than the net working capital itself.

Thus, a positive difference between cash and working capital implies excess cash—funds available beyond immediate operational needs.

#3) Industry Average

Another option is using the industry average Cash/Sales ratio, and considering anything above that in the company you’re analyzing a cash excess.

Under this idea, if your company’s cash and cash equivalents are below industry standards, it has no excess cash.

Now that you have an idea of how to calculate excess cash from balance sheet, it’s also important to know what companies do with excess cash:

What Do Companies Do with Excess Cash

Firms have many options for managing excess cash on their balance sheets. Here are the common things they can do:

- Invest in new projects and growth opportunities: The company can research and develop new products or technologies, expand into new markets, or invest in infrastructure and capital expenditures into fixed assets to increase production capacity. The goal? Better competitive position and higher returns for investors.

- Acquire other companies: M&A allows companies to leverage their surplus cash to fuel growth and achieve strategic objectives.

- Pay off debt: Paying off outstanding debt obligations improves the financial stability of the firm thanks to lower interest expense and better creditworthiness.

- Payout to investors: Companies can also distribute excess cash to their shareholders in the form of a dividend or share buyback.

Too much excess cash holdings may correlate with a lack of growth opportunities.

The specific decisions regarding excess cash management vary from company to company and depend on the financial position, growth prospects, industry dynamics, and overall strategic objectives.

Now, here’s why excess cash impacts valuations:

How Excess Cash Impacts Valuation

When valuing a company, analysts should estimate excess cash and treat it separately since it is a non-operating asset.

Let’s go through some common valuation components that excess cash affects:

Starting with the Discounted Cash Flow (DCF) model, to get the operational cash flow and estimate the Free Cash Flow to the Firm (FCFF) you’ll want to exclude any non-operational revenue from EBIT to get the business’s intrinsic value.

For example, interest earned on savings accounts is a non-operational revenue. Unless you’re analyzing a financial institution or something.

Also about the FCFF, when subtracting the working capital variation you’ll want to consider only operational items in current assets and liabilities (as opposed to the total current assets and the total current liabilities) when calculating the working capital value for each year.

In practice, these items are usually accounts receivable, inventory, non-excess cash, accounts receivable, and tax advances.

Moving on:

The Enterprise Value of a business is its Equity + Debt – Cash, right? You can think of it as the price to pay to acquire a company. Here, cash represents the liquid assets of the business that the acquirer can use to reduce the acquisition cost. But this begs the question:

Should all cash be considered?

We’ve just seen that the answer is no. You should deduct only the cash not used to fund business operations—the excess cash.

The business must keep a minimum amount in order to be able to function properly.

Naturally, this adjustment will also affect the EV/EBITDA multiple, widely used for relative valuation.

In the Equity Value, you add Non-operating Assets to the Enterprise Value and subtract Net Debt.

Why do we add the non-operating assets? Because a potential acquirer can sell them by their market value. The difference between the market and accounting value creates a positive or negative tax effect.

As extra cash is a non-operating asset, you also subtract it in the Equity Value computation (without the tax effect obviously).

Lastly, what you consider excess cash holdings will also impact the Return on Invested Capital (ROIC), which tells you how efficiently a company uses the money it receives from its shareholders and debtholders.

You calculate it by dividing the NOPLAT by the Invested Capital (IC). And the IC is calculated as: Equity book value + Financial debt – Non-operating assets.

Some analysts consider the entire cash and cash equivalents a non-operating asset and remove it. But is it all an operating asset? No. Only excess cash balance.

Treating the entire cash balance as a non-operating asset (instead of recognizing a portion is needed for working capital purposes) is a mistake. The company always needs some part of the cash for its operations.

In conclusion, how you define what is excess cash will have a great impact on the valuation of a business.

Key Takeaways (FAQs)

How do you define excess cash?

Excess cash in business is the extra money a company has beyond its operational needs. Companies can use excess cash to fund attractive internal or external opportunities.

What is considered excess cash on a balance sheet?

Any cash above what the company needs for its day-to-day operations. Also, balance sheet items under cash and cash equivalents that are considered excess cash for their nature itself are usually marketable securities—such as stocks, bonds, treasury bills, a money market fund, and commercial paper—all of which have nothing to do with the business’s core activities and can be easily converted to cash.

What is the rule of thumb for excess cash?

The rule of thumb for excess cash is to include 2% of revenue as necessary cash for a company that has reached a mature state. For early-stage companies, a ratio of cash to revenue of 5% may be appropriate.