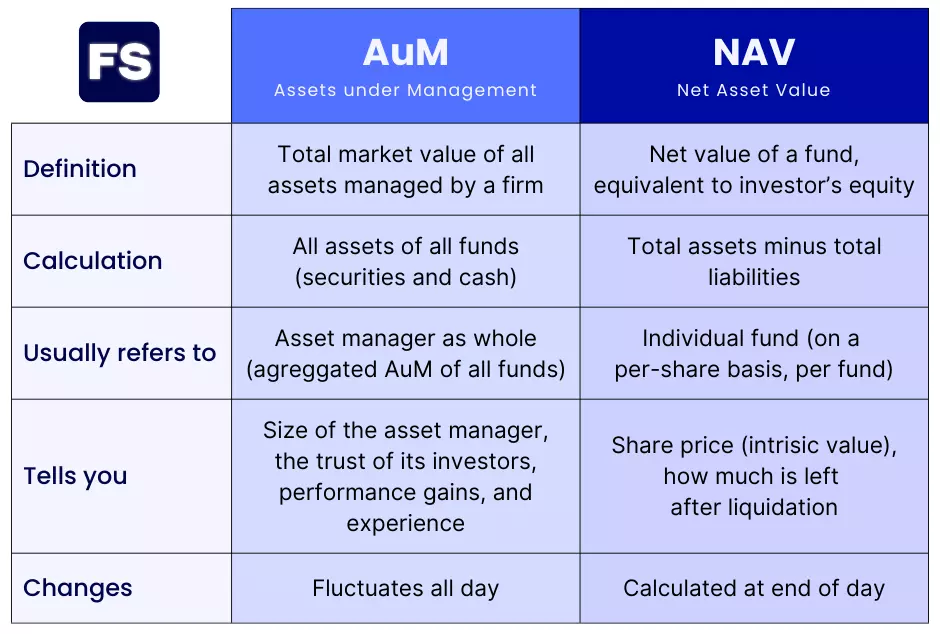

AuM is the total market value of the assets an asset manager oversees on behalf of its investors. It includes stocks, bonds, and cash within the funds the asset manager manages. AuM doesn’t subtract unpaid expenses. NAV on the other hand, does. It is the total assets minus liabilities of a fund.

At first glance, the two metrics appear similar. But a closer look reveals key differences:

That’s the gist of it.

For a more comprehensive answer, keep reading:

What Is AuM (Assets under Management)

Assets under management (AUM) is the market value of the investments managed by a firm on behalf of its investors.

The asset manager receives funds from clients and allocates money to investments (whether stocks, bonds, or derivatives).

AuM fluctuates according to two things:

- Flows of money in and out of a fund. (New investors joining and/or old investors leaving.)

- The market price performance of the assets the fund invests in.

In general, the higher the AuM of an asset manager the better. Why?

Because it signals the manager has earned the trust of investors, so they keep pouring more money in. And also performance gains from picking the right investments.

Different firms may calculate the AuM differently, but in general it is the AuM from the previous year plus subscriptions, minus redemptions, plus/minus investment performance.

Keep in mind AuM does not include assets of the management company itself, such as accounts receivable, property, stakes in other companies, and cash. These items are part of the company’s own balance sheet.

For clarification, the company collects money from investors and may decide to not invest it (wait for better opportunities). In this case, cash is part of the portfolio and counts toward the AuM. The cash in the balance sheet as a result of past revenues (from charging fees to clients) does not.

AuM also does not take into account the balance sheet liabilities, such as lease agreements and accounts payable.

Also, asset managers charge fees to their clients based on their AuM, so the higher the AuM the more fees the firm collects.

New subscriptions, capital gains, and interest/dividend payments increase the AuM of a fund, while capital losses (poor investment performance) and investors’ redemptions decrease it.

As such, AuM is not the best indicator of how good the asset manager is at picking investments.

This is because if dividends paid to investors or redemptions are higher than the growth in assets due to good performance, the AuM still decreases.

AuM is best used to assess the size of an asset manager and the investors’ trust that size implies.

What Is NAV (Net Asset Value)

The Net Asset Value (NAV) is the total value of a fund’s assets minus its liabilities.

It is commonly used in the mutual funds industry, as a measure of the fund’s intrinsic value. And it is typically presented on a per-share basis.

Again, a fund collects money from its investors and puts it into securities (such as stocks and bonds), in hopes of growing the funds and providing a return to investors.

Those securities and cash are the assets of the fund.

The market value of the securities in which the fund invests is usually the overwhelming majority of its assets.

Other assets a fund may have include subscriptions and fees to be received, dividend/interest payments to be received, and unrealized gains on derivatives contracts.

But what liabilities does a fund have?

These are usually very small when compared to the assets. They include bank overdrafts, accrued expenses (expenses taken but not paid yet), live losing positions in derivatives contracts, and payable amounts on repurchase agreements.

Net asset value per share (NAVPS) is the end-of-day market value (closing price) of the securities in the fund, plus the value of any additional assets the fund may have, minus its liabilities.

To get the NAVPS, managers divide this difference by the number of outstanding shares.

This value differs from the fund’s actual market price (for closed-end funds), since NAVPS is calculated once per day, while the fund’s assets change in price throughout the day.

When the fund is open-ended, the NAV represents the price at which you can buy or sell shares in the fund (not taking into account any entry or exit fees).

An open-end fund can issue new shares to investors, does not trade publicly, and is priced each day at the close of trading at their NAV price.

Closed-end funds on the other hand, trade on a public exchange. And supply and demand determine their share price throughout the day (just like the stock price of a publicly traded company), not the NAV.

Now, the market price may reflect a premium or a discount to the underlying value of the fund (NAV), which is a potential loss but also a potential gain for the investor.

Similar to AuM, NAV is not the best measure of the performance of a fund. Why?

Because funds often pay investors the interest and dividends the fund receives from its investments, as well as capital gains. As a result of these cash flows, the NAV of the fund drops accordingly.

Therefore, comparing the NAV of a fund between two dates to analyze its performance is incorrect. An investor may have received income and returns between the two dates, while the NAV decreased.

A better way to measure fund performance is by looking at the returns of the securities within the portfolio picked by the manager.

NAV is good for assessing the credit risk of a fund, as it is the cash left in case of liquidation of the fund—similar to the shareholders’ equity of a company, or the net worth of an individual.

Difference between Net Asset Value and Assets under Management

Both metrics measure the size of investment funds, whether mutual or hedge funds.

NAV is the total value of a fund’s assets minus all its liabilities. NAV per share tells you the price at which you can buy and sell shares in a fund (unless the fund trades publicly).

In contrast, AuM typically refers to the total value of all the assets a firm manages, as opposed to a single fund. Although it can refer to a single fund, but never on a per-share basis.

Likewise, analysts also use the aggregated NAV of all the funds of an asset manager, especially when assessing the creditworthiness of said asset manager.

In essence, AuM is more common to see how much money an asset manager controls in total. NAV is more common when analyzing individual funds.

NAV is not the AuM divided by the number of shares.

AuM is not the sum of all NAVs of all the funds of an asset manager.

Here’s why:

Unlike the NAV, AuM doesn’t subtract the liabilities of the fund. And in both NAV and AuM balance sheet items of the company itself do not matter. Although the calculation may vary from firm to firm.

Still, the difference between the aggregated NAV and AuM of an asset manager is most times insignificant. Why?

Because the main asset (the investments in securities) completely overwhelms the liabilities a fund may have, unless it uses excessive leverage and has outstanding losing derivatives positions and high management costs.

So, AuM is higher than the NAV when the fund has a lot of debt and outstanding payments.

Although it’s not common to highlight the AuM of a single fund, the NAV is simply the AuM of a fund minus its liabilities.

NAV is the equivalent of equity (assets minus liabilities) in a balance sheet of a fund, while AuM is more like the cumulative net income from an income statement of subscriptions, redemptions, and investment performance.

Both metrics are not the best to assess investment performance (how good the portfolio managers are at picking stocks and bonds to invest in) because investors’ cash inflows and outflows also impact them.

Now, what about when a fund has more than one asset manager?

Imagine an asset manager A who delegates the management of 50% of the money in a fund (€100M) to another asset manager B.

In this case, both asset managers have an AuM of €50M each. But only asset manager A has an NAV of €100M (assuming the fund has zero liabilities).

Although this depends a lot on the legal agreement between the two firms, generally only asset manager A is liable to pay in case of default of the fund. Asset manager B is only there to make investment decisions, and is not responsible in case the fund collapses.

So basically asset managers use AuM to say: “Look at how much money we control, this is how much we have the power to decide to invest with.”

And NAV to say: “In case we trade derivatives with you and we get obliterated to zero, this is how much we can pay you after selling everything we have in the fund. This is the fund’s net worth.”

Hope this helps.

Questions? Doubts? Feedback? Let me know in the comments below.