Options are financial derivatives that allow you to hedge the risk of an existing position, or speculate on the price movements of a stock.

There are many option strategies you can use to achieve different goals.

In this post, we’ll look at what is a protective put, what is a covered call, and what are the differences and similarities between the two.

Wondering when to use each? Keep reading:

What is a Protective Put?

A protective put is a hedging strategy used to mitigate the risk of holding a long position in a stock (or another underlying asset).

It consists of buying the stock and buying a put option.

When you buy a put, you get the right to sell the stock you already own at a predetermined price.

This means you can guarantee the worst-case price at which you sell the stock, without limiting the upside potential of the stock going up.

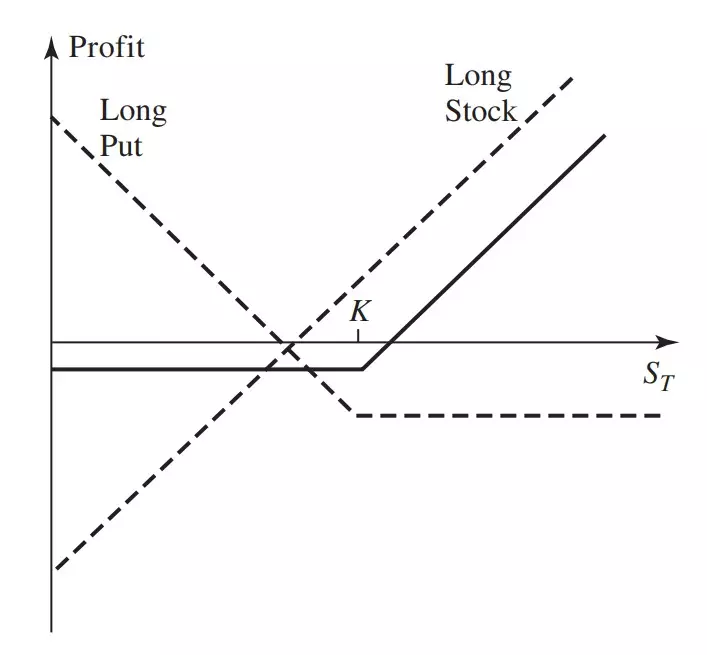

You reduce the upside but you don’t limit it, like some other option strategies. A flat horizontal line in the payoff profile would represent a limited upside. Instead, we have a diagonal straight line going up without end off to the right:

Protective Put Payoff Profile

K is the strike price of the put option. The price at which you bought the stock is the x-intercept of the Long Stock payoff line.

The higher the strike of the put, the more protection you get.

Knowing this, all you need to do to not lose money in your long stock position is get the right to sell it for higher than what you bought it, right? In other words, a put option with a strike higher than the price at which you bought the stock.

Well, you have to pay for that right.

The cost of the protection is the premium paid for the put, and more protection is more expensive.

Now:

As the holder of a long position in a stock, you want it to go up.

If the stock price rises above the strike price of your protective put, you don’t exercise it. Instead, you sell the stock on the market for higher.

If you don’t exercise your put, you don’t use the protection you bought. What happens in this case? Nothing. Only the profit is lower than that of a naked (unprotected) long stock position because of the protection cost.

Let’s look at an example to solidify these concepts:

Protective Put Example

Say you have 100 Apple shares you bought some time ago for $100 each. Today, the stock trades at $110. You believe the stock will continue to go up in the next 3 months, but you want to protect your current potential profit of $10 per share. What can you do?

You can buy a put with a strike price of $110 and expiration in 3 months’ time.

With this, you guarantee you’ll sell the 100 Apple shares for at least $110. But the protection has a cost.

If Apple trades above $110 at expiration, your protection is worth nothing. You can sell the shares directly in the market for more. Your profit is the current stock price minus the price at which you bought it, minus what you paid for protection.

If it trades below $110, you can sell the shares for $110 by exercising the put option. Your profit is $10 minus what you paid for the put.

What is a Covered Call?

A covered call is when you sell a call option while holding a long position in the underlying asset.

Generally, the goal is to take advantage of small decreases in the price of a stock by collecting premium from the sold call. But you may also use this strategy when you want to hedge a short call position, and so you cover it by buying stock.

As you sell someone the right to buy the stock from you at a predetermined price, you must have the stock in case they exercise their option.

It’s possible to sell a call without holding the stock. If your counterparty exercises their option to buy stock from you, you would then buy the stock at the current market price with the sole purpose of selling it to them and holding your end of the contract.

In a covered call, you already own the stock. See the difference? In general, you have 100 shares, as that’s the most common contract size for stock options.

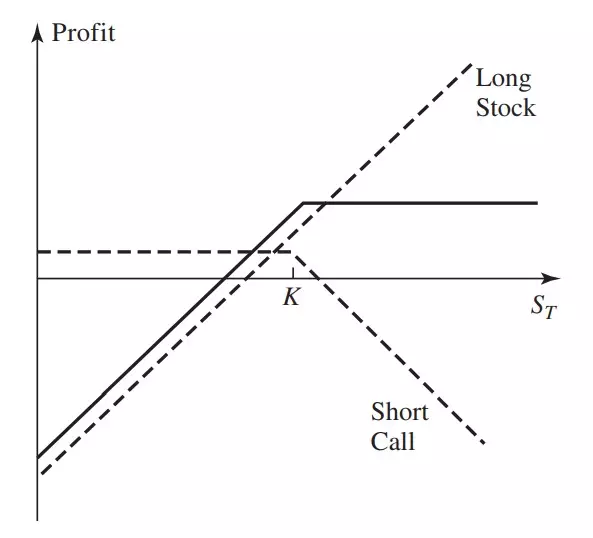

Covered Call Payoff Profile

This payoff profile illustrates the perspective of hedging against a short call position. It assumes you buy the stock and sell the put on the same day, and that you will sell the stock at expiration no matter what.

If the price of the stock is above the strike price of the option at expiration, your counterparty will exercise its right to buy the stock for cheaper from you.

Even though you have to sell the stock for cheaper than the market, you’re selling it for more than what you bought it for. That difference, combined with the premium you collected when you sold the call, is your profit.

In case the stock price is below the strike price of your put, you may be in trouble. Here’s why:

The call you sold is now worthless, as your counterparty can simply buy the stock for cheaper from the market. This is good. You collected the premium and that’s it.

The problem is in your long stock position. It lost value due to the price decrease, so you’re losing money.

In the payoff profile above, you sell the stock and take the L.

However, in reality? You likely won’t sell the stock. You’ll wait for it to recover.

Selling Covered Calls for Passive Income

Most people write covered calls as a way to collect so-called passive income.

Every week, they sell call options on stocks they already own, and for which they are bullish long-term. Solid companies they believe will continue to grow.

The goal is to take advantage of small declines in price today and collect premium. So, they repeat this every week, until one day the stock goes up enough and they actually have to sell. They’ll do it for a profit though.

Sounds like an arbitrage opportunity, right? It’s not. Maybe I made it sound too good and look like they can’t lose.

Remember: The stock price may never recover from going down, in which case they’ll have to take the loss. Even though that loss is cushioned by the premium collected, it’s still possible to lose money. In theory, a stock’s price can drop all the way down to 0. That’s what the graph displays with the never-ending line off to the left.

This is why it’s important to choose stocks of well-established companies you think will continue to grow in the future.

Covered Call Example

You own 100 shares of Apple, bought for $100 each. You’re bullish on the stock long-term, but in the next few months? You think the market as a whole will take a hit, and Apple’s stock price will drop with it. Can you take advantage of this? How do you protect your long stock position from short-term decreases in price?

By writing a covered call. So, you sell a call for 100 shares with a strike price of $120.

Why an OTM strike? Because the goal is for the call option you sell to expire worthless. The further OTM the call you choose is, the less probability it will end in the money. At the same time, the less premium you receive.

If it ends in the money, you’ll have to sell the stock you bought. Even though it will be for a nice profit ($20 per share), your profit is limited to $20 even if the stock goes to $300.

Protective Put vs Covered Call

So, what’s the difference?

Both strategies have two things in common:

- A long position in the underlying asset.

- The goal of dealing with a price decrease in that asset.

What they don’t have in common is the common intent behind the strategy.

A protective put protects you against a fall in the price of your stock by offsetting your payoff with a put. If the stock falls, you make money on the put because you have the right to sell the stock for higher than its market price.

A covered call is speculative. You’re betting the price of the call won’t go high enough for you to have to give up your shares. In the process, you collect premium.

Key Takeaways

Here are the main ideas you need to grasp to understand the difference between a protective put and a covered call:

- A protective put consists of a put option combined with a long position in the underlying asset. Its goal is to hedge a long asset position against price decreases.

- It functions like insurance, where you pay the premium price to reduce the impact of a fall in the price of the stock you own.

- A covered call is a long position in a stock combined with a short position in a call.

- It’s called covered because you already own the shares you need to sell to your counterparty for the predetermined price (in case they exercise).

- Generally, the goal is to generate additional income in the form of premium from the stocks you already own.