Options are financial derivatives traded over 40 million times every day. Knowing that, you may be wondering… What’s all the fuss about?

Calls? Puts? Strike price? In-the-money? OTM? Intrinsic value? Premium? What does all this jargon mean?

In this article, you’ll learn everything you need to know to master the basics of financial options, even as a beginner.

This post is the ultimate guide to understanding options for dummies. I’ll explain what are options in simple terms.

Wanna know how do options work? Let’s dive in:

What is an Option?

An option is a financial contract that gives you the right to buy or sell a certain amount of some financial asset, for a predetermined price, at or until a future date.

There are a few key concepts you must know to understand what is an option:

- A call option gives you the right to buy an asset by a certain date for a certain price.

- A put option gives you the right to sell an asset by a certain date for a certain price.

- The asset you want to buy or sell is the underlying asset.

- The contract size refers to the quantity of underlying asset you want to buy/sell.

- Strike price (or exercise price): The price you agree to buy/sell the underlying asset for.

- Expiration date (or maturity date): The contract expires on this date. After this date, you can no longer exercise what’s in the contract.

For example, how do you categorize the right to buy 100 shares of Microsoft for $120 each on June 16th 2023?

It is a call option, for which the underlying asset is Microsoft stock, the contract size is 100, the strike price is $120, and the expiration date is June 16th of next year.

Now, when it comes to the expiration date, options have two different styles:

European Options vs. American Options

Options can have different styles: American or European—a distinction that has nothing to do with where you live. It also has nothing to do with the two types of options—calls and puts.

American option refers to a contract you can exercise at any time up until the expiration date. From the moment you buy the contract to the moment it expires, you can enforce what’s in the contract whenever you feel like it.

On the other hand, European options can only be exercised on the expiration date itself. They can’t be exercised before that.

Exercising means converting the contract into shares at the strike price.

Most of the options traded on exchanges are American. However, European options are easier to analyze, as they maintain put-call parity.

What are the Different Types of Underlying Assets?

In theory, anything can be used as an underlying asset. But the most common are:

- Stocks: Stock options refer to options for which the underlying asset is a company’s stock.

- Indices: When the option contract refers to a stock index like the S&P 500 or Dow Jones.

- ETFs (Exchange Traded Funds): These are portfolios of assets that trade like a stock. They too, can be used as the underlying asset of an option contract.

- Futures: Options on futures contracts following the price of anything from oil, to gold, to corn.

- Foreign Currencies: Options on foreign currency exchange rates.

- Interest Rates: Options that allow you to benefit from changes in the rate of bonds like U.S. Treasury securities.

I will sometimes refer to stocks as the underlying asset from now on for simplification’s sake, as they are the most common underlying asset for options contracts.

Basic Option Positions

There are 4 types of options positions:

- A long position in a call option.

- A long position in a put option.

- A short position in a call option.

- A short position in a put option.

Long position means buying. Short position means selling.

Long positions are straightforward. But, short positions? Maybe not.

As the buyer of a call option (holder of a long position), you get the right to buy a stock for a predetermined price at a future date.

Here’s the deal:

Whenever you buy a call option, there’s someone on the other side of that trade.

They commit to the agreement between the two of you. They are obligated to sell shares to you at the predetermined price if you choose to exercise the contract.

You can do that too. You can be the person on the other side. As the holder of a short position, you can sell someone:

- A call: The right to buy a stock from you at a fixed price in the future.

- A put: The right to sell a stock to you at a fixed price in the future.

This is also called writing. You’re the one writing the contract.

Now, why would you do this? Why would you take the chance of having to sell or buy an asset at an unfavorable price because someone else said so?

Because you receive a premium:

Stock Options Contract Premium

Premium is the price the buyer pays for the contract. It’s the cost of the privilege to buy/sell a stock for whatever you want whenever you want.

As you can imagine, the more advantageous the contract is for the buyer, the more the seller will want to receive in premium. No such thing as free lunch.

Although the strike price of the contract and the price of the stock influence the cost of the contract (premium), these are 3 different things.

As the buyer, you pay just to open the contract. Think of it as the price to pay for the sheet of paper that holds the terms of the option contract, if everything wasn’t as electronic and automatic as it is today.

Let’s look at an option chain with call and put options examples to further understand this.

An option chain lists all the available options contracts for a given security. It shows all listed puts, calls, their expiration, strike prices, volume, and pricing information (premiums).

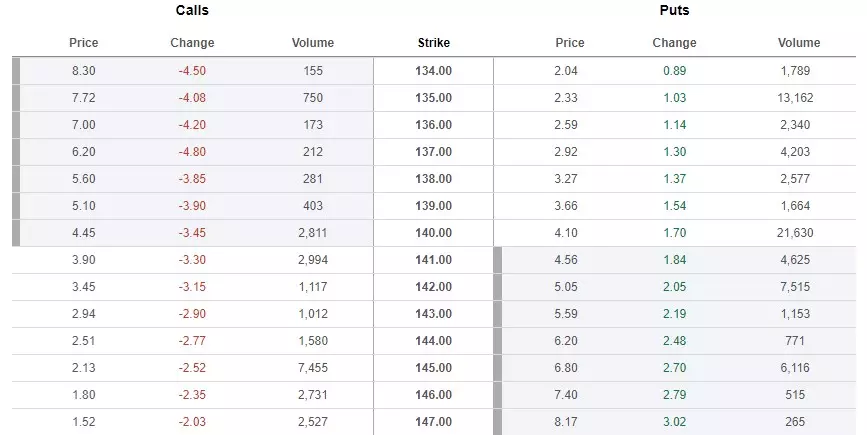

The following image is the option chain for October 21st 2022 Apple options. On this day, Apple fell 3.67% to $140.09 (last price at the close, October 7th).

On the left, we have the calls. On the right, we have the puts. All options have a contract size of 100, and a single expiration date—October 21st. The option style is American.

The prices are for 1 share of Apple. Since the contract size is 100, the actual amount involved in the transaction is 100 times the prices displayed.

Notice how the option price changes with each strike price.

The price of calls decreases as the strike increases (having the right to buy Apple shares for cheaper at $135 is more valuable than at $145).

Whereas the price of puts increases as the strike increases (having the right to sell Apple shares for more, like $145, is more valuable than for $135).

Options’ premiums are constantly changing to reflect price movements in the underlying asset.

The Change column tells you the variation of the premium compared to yesterday. Since Apple had a red day, you can see that call option contracts lost value. Meanwhile, puts got more expensive.

Why did this happen?

Say you have one call option with a strike price of $138—the right to buy Apple for $138. If Apple’s stock price drops below $138, meaning you can buy Apple in the open market for cheaper than what’s in your contract, why would you exercise the contract?

How much is the contract worth? What’s the value of being able to buy something for a high price, when you can get it for cheaper somewhere else? It’s worth nothing. The contract is worthless.

Well, as the stock price drops, that scenario becomes more of a possibility, and the premium reflects it accordingly. That’s what happened in the option chain above.

If the stock price shoots back up, call prices will rise with it. The right to buy for cheaper is now more valuable, as the stock got more expensive.

It’s the same for puts. As the stock price falls, the right to sell it for more than what it trades on the market becomes more valuable.

If you’re not hedging an existing position, this means that as a:

- Call option buyer, you want the stock price to go up.

- Put option buyer, you want the stock price to go down.

- Call option seller, you want the stock price to go down, or stay the same.

- Put option seller, you want the stock price to go up, or stay the same.

Payoff diagrams show you when an option is more or less valuable:

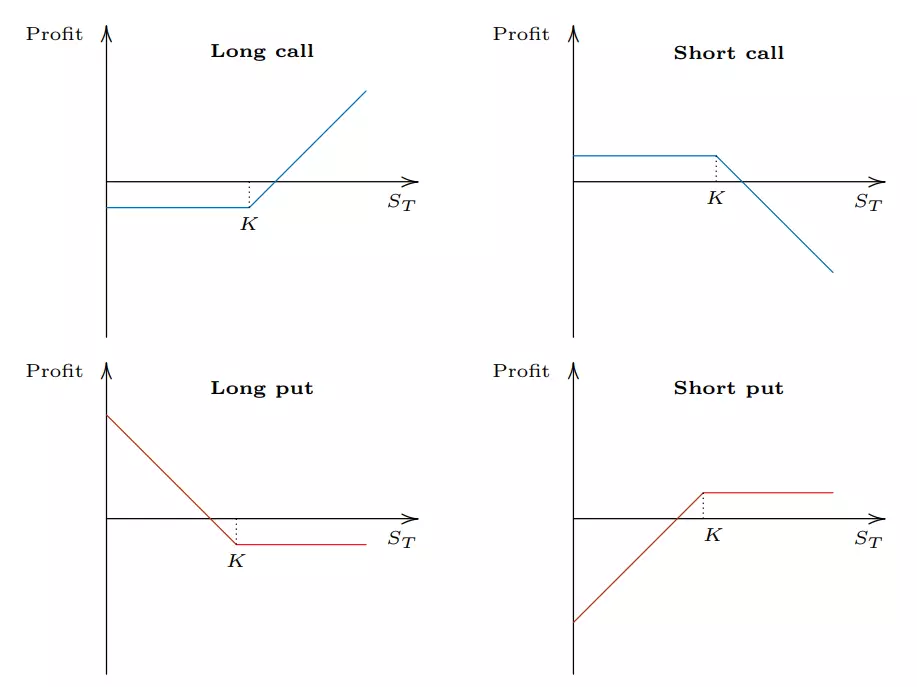

Options Payoff Diagram

A payoff diagram is a graphical representation showing you how much money you’ll make given a scenario at the expiration of an option contract.

The option payoff is the cash flow the option contract generates at the expiration date (European option) or at the exercise date (American option).

Here’s the payoff diagram for the 4 basic option positions:

The X-axis represents the profit from the strategy at expiration (or when you exercise the contract).

The Y-axis is the market price of the underlying asset (ST) on that date. K is the strike price chosen for the contract. When the price at which the asset trades on the market and the strike match, it means ST = K.

Let’s look at each scenario to help you further understand what are options and how do they work:

Long Call

The payoff of a long call depends on if you exercise it or not. You only exercise it when the price of the stock is above the strike price.

In that case, you pay K (less) to receive an asset worth ST (more). Your profit is the positive difference between the strike price and the stock price, minus the premium you paid for the contract.

As the stock goes up, you have the right to buy for cheap. That’s why the profit keeps growing off to the right to infinity. Theoretically, the price of a stock can grow to infinity.

If the stock price is below the strike price at expiration, the contract is worthless. Why? Because it gives you the right to buy for the strike price when you can go to market and buy it for cheaper. Your loss is the premium you paid for the contract.

Long Put

The long put gives you the right to sell a stock for the contract’s strike price.

At expiration, how much do you want that stock to be worth? Zero.

If the stock goes down, you can go to the market, buy it for cheaper, then exercise your option and sell it for higher. In other words, you receive the agreed strike price in exchange for an asset worth less than that.

Your profit is that positive difference, reduced by the premium you paid for the contract.

If the stock is above your strike price at expiration, the right to sell the stock for the strike price is worthless. You can go to the market and sell it for more. Your loss is the premium paid.

Short Call

You sold the right to someone to buy the stock for the strike. Buy from who? Buy from you. You’re obligated to sell the shares for the strike price, if your counterparty chooses to exercise their right.

At expiration, if it’s favorable for them to exercise their right, it means it’s unfavorable for you.

Say when the call option (strike $110) you sold expires, the underlying asset is worth $120. This means you have to go to the market, buy the asset for $120, sell it to your counterparty for $110, and take the loss of $10. The premium you received from the buyer beforehand mitigates the loss, but it’s still a loss.

This is why the best-case scenario for a short call is for the price to stay the same or go down. You collect the premium and nothing happens after that.

The worst-case scenario is an astronomic loss, because the stock price can theoretically go up without a limit.

This is the main downside of short positions on any security—when you buy an asset, the worst that can happen is it goes to zero. But when you sell it with the intent of buying it back later? There’s no limit to how much you’ll have to pay to buy it back.

Short Put

A short put means you sold someone the right to sell stock to you.

If they don’t exercise their right, it means the stock was above or equal to the strike at expiration. Their right to sell below the market is worthless. You keep the premium you collected at first and nothing happens.

If they exercise their right, it means the stock price dropped below the strike price of the put contract. You pay the strike price (for example, $50) to the buyer of the contract and receive shares. The problem? Those shares are trading below $50. You paid $50 for something worth $40.

The good news is your $10 loss is not as big because, at first, the buyer paid you some premium to get into the contract.

What does Moneyness mean in Options?

Moneyness is tied to the intrinsic value of an option contract.

What is intrinsic value?

Intrinsic value reflects the gain from the immediate exercise of an option. It is the positive difference between an option’s strike price and the price of the underlying asset. It exists if the strike price is below the current market price for calls, and above for puts.

Why is it called intrinsic value?

Because there are other factors not related to the asset’s market price that influence the value of an option. We call it extrinsic value, and its main components are:

- Time value: How much time do you have until expiration?

- Volatility: How aggressively does the price of the stock swing (up or down)? How likely are you of getting a big move in your favor?

- Interest rates: How much do you get for putting your money in the bank instead of buying options contracts?

- Dividends: Will the stock pay dividends between the time you open the contract and its expiration?

All extrinsic factors are worth zero at expiration. Only the intrinsic value holds—if there’s any.

Now that you know that, you can better understand moneyness:

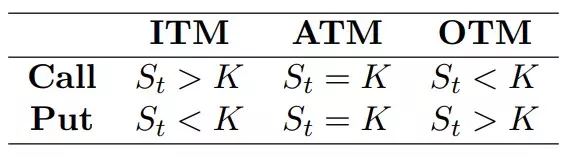

At expiration (or at the exercise date), an option is:

- In-the-money (ITM) if it generates a positive payoff. It has intrinsic value. This is the only situation where the buyer of an option will exercise their right.

- At-the-money (ATM) if it generates zero payoffs. It has no intrinsic value. The strike price is equal to the price of the underlying asset.

- Out-of-the-money (OTM) if it generates a negative payoff. It has no intrinsic value. The intrinsic value can’t be negative because the option gives you a right, not an obligation to exercise what’s in the contract.

In the option chain above, the shaded area has options in-the-money.

Difference between Options and Forwards and Futures

A forward is a contract between two parties agreeing to buy/sell a certain asset for a certain price at a certain future date. It is highly customizable and negotiated privately.

A future is the same thing, but it is standardized and traded on a public exchange.

Options and forwards/futures are similar in every way except for one thing:

In a forward/future both buyer and seller have the obligation to trade the underlying asset at the expiration date for the agreed price. They are forced to do it.

What will happen at the expiration of a forward/future is always certain. The buyer will buy/sell for the strike price. The seller will sell/buy for the strike price. That’s it. It’s the reason why payoff profiles for these instruments are much more straightforward than for options.

In the option contract, only the seller has an obligation to trade the underlying asset. The buyer of the contract has the right (not the obligation). The buyer can trade the asset or not.

If the buyer decides to exercise their right to trade the asset, the seller is forced to be the counterparty on that transaction.

When will the buyer exercise their right?

When the option has intrinsic value—which depends on the price of the underlying asset at expiration. This uncertainty is the reason why payoff diagrams for options are more complex.

Unlike options, forwards have no setup cost—you don’t need to pay a premium for the contract. Here’s why option contracts have a cost, while forwards don’t:

The holder of the long position in an option will only exercise its right when it’s advantageous to them and, consequently, disadvantageous to the seller.

How can the buyer convince the seller to get into the contract?

By paying a premium for the contract itself, as we’ve seen above.

For example, imagine you buy a put with a strike of $150. At expiration, the stock trades for $160.

The put gives you the right to sell for $150, so why not go to the market and sell it for $160 instead? Your put is worthless and you won’t exercise it.

With a forward, you are forced to sell below the market. No matter what.

As the buyer, the choice to exercise your right or not gives you an advantage over the seller. With premiums, you have a level playing field.

Options Trading Example

Let’s run through a simple example of buying a call option. We’ll look at the setup, payoffs, contract size, moneyness, and how premium affects profits and the break-even point.

You believe Apple’s stock will rise above $145 in the near future. So you buy 5 call options with a strike price of $145 expiring in October. Each contract costs $2, and the contract size is 100.

So each contract costs you $200. $1,000 total.

What does each option contract give you?

It gives you the right to buy 100 Apple shares for $14,500 until October.

Since you bought 5 contracts, you have the right to buy 500 Apple shares for $72,500 ($145 for each share).

Currently, Apple trades at $140. Your call option is OTM, which means it has no intrinsic value. The $2 you paid in premium is purely extrinsic value.

We’re hoping this changes—we want the price of Apple to rise so your call options expire ITM.

Expiration is here.

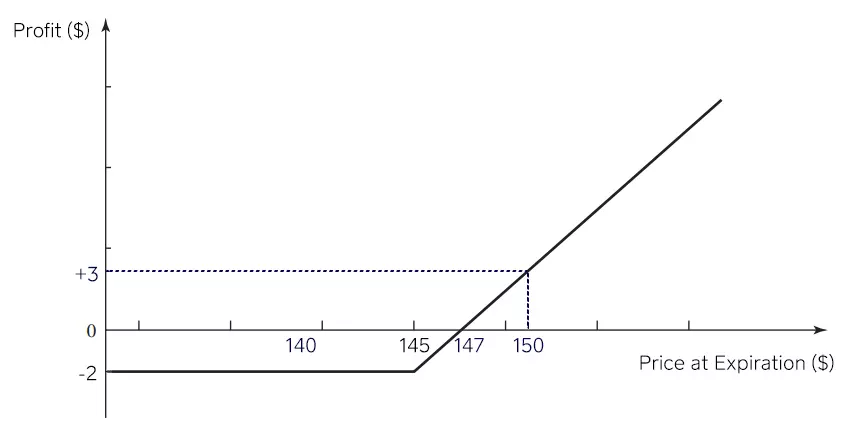

Apple now trades at $150. Did you make money? Here’s the profit profile:

Yes, you made money. Let’s break it down:

Your call option is ITM and has an intrinsic value of $5. This means, you now have the right to pay $145 for an asset worth $150.

So, you exercise all 5 call options and buy 500 shares for $72,500. Who’s selling them to you? The holder of the short position on your calls, that is, the person who sold you the contracts. They are obliged to hold their end of the deal and take the loss.

You can then go to the market and sell your 500 Apple shares for $150 each, for a total of $75,000.

How much did you make? $2,500. But remember, you paid $1,000 for the 5 contracts in the first place. Your net profit is $1,500, or $3 a share.

The profit profile takes the $2 premium cost into account. This is why the break-even point is $147.

If the call expired and Apple traded for $147, your option has an intrinsic value of $2. You can exercise your right to buy 500 shares for $145 and sell them for $147 immediately after on the market, making a gain of $1,000. However, $1,000 is exactly what you paid for the 5 calls, so your net profit is $0.

It could be worse:

If, at the time of expiration, Apple trades below 145, your loss is the premium you paid for the call option. That $1,000 are gone, and you won’t get them back. The seller of the call is happy.

Thanks for reading. I hope this helps!

Questions? Doubts? Feedback? Leave them in the comments below.