It depends. If you want to evaluate the company’s ability to meet short-term obligations, you calculate working capital as the difference between total current assets and current liabilities. Current assets include cash and cash equivalents. If you want to compute the intrinsic value of a company and are calculating the FCFF, you should exclude all non-operational items. This also applies to the working capital variation. Thus, excess cash should not be included.

That’s the gist of it.

Want a more comprehensive guide on the components of working capital? And if is cash included in working capital calculation? Keep reading.

What Is Net Working Capital

Working Capital (WC), also known as Net Working Capital (NWC) is the capital required in the short term to run a business.

It is the difference between:

- Current assets, such as cash, inventory, and accounts receivable.

- Current liabilities, such as accounts payable, short-term debt, and taxes payable.

Analysts use this difference as a measurement of the short-term liquidity and health of a business. You can also calculate the Working Capital Ratio = Current Assets / Current Liabilities.

Working capital is always changing.

By the time its financial statements come out, the working capital position of a company has likely already changed—at least from an accounting perspective.

But from a financial perspective, a business is a renewable never-ending cycle of purchases, production, storage, and sales.

Thus, these items are permanently on the balance sheet.

Every day existing clients are paying past sales, new sales are made, and new credit is given to clients.

For instance, if a company gives its clients 1 month to pay their invoices, whenever you look at the balance sheet what will you find under accounts receivable? A month’s worth of sales the company is yet to collect payment for.

The same applies to inventory and accounts payable.

If the payment conditions don’t change drastically, these items have a short life in terms of accounting. In reality? They are always present in the balance sheet.

This allows us to conclude:

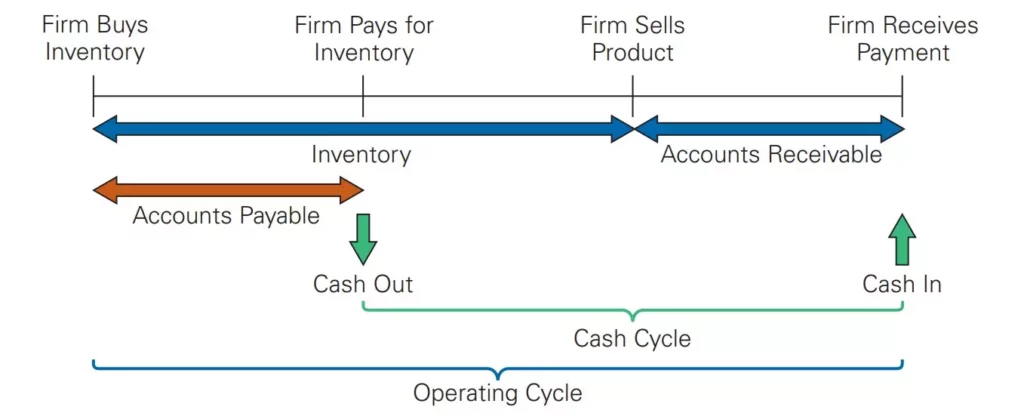

Working capital reflects the length of time between when cash goes out of a firm at the beginning of the production process and when it comes back.

The process goes something like this:

- The company buys inventory from its suppliers, in the form of either raw materials or finished goods. And it will typically buy on credit, which means the company doesn’t have to pay cash immediately at the time of purchase.

- After receiving the inventory, it may stay with the company for a while until a customer is interested. This varies from industry to industry.

- Finally, when the inventory is sold, the firm may give credit to the customer, delaying when it will receive the cash inflow.

Thus, a company’s cash cycle is the length of time between when it pays for inventory and when it receives cash from the sale of that inventory.

The operating cycle is the time between when the company buys inventory and when it receives the cash back from selling its product.

If it pays immediately for the inventory (does not receive credit from suppliers), the operating cycle is the same as the cash cycle. This is rare.

Most companies buy their inventory on credit, which reduces the time it takes between the cash outflow and the subsequent cash inflow.

The longer the cash conversion cycle, the more working capital the company has.

The more positive working capital, the more cash on hand is needed to execute daily operations.

In contrast, companies with short (or even negative) cash cycles are constantly receiving payments from customers. The result? They don’t need as much working cash balance available.

Now with this in mind, there are two ways to calculate net working capital:

How to Calculate Working Capital

As we’ve seen, to calculate working capital, you subtract current liabilities from current assets.

The question is, should you include all current liabilities and assets?

You have two options:

#1) Total Current Assets and Liabilities

If your goal is to analyze the short-term liquidity of the company, or its ability to cover its immediate obligations, then use the following working capital formula:

If the company you’re analyzing is publicly traded, you can easily find this information in the balance sheet. For private companies however? It may not be as readily available.

Working capital is stated as a dollar number.

When the number is positive, the company has more than enough resources to cover its immediate obligations. If it converted all of its current assets into cash, and paid the commitments under current liabilities, there would still be cash left.

When the number is negative, the current assets are not enough to pay for all the current liabilities. The company has more short-term obligations than short-term resources. Is this good or bad?

It’s bad because you’re considering all current assets, including cash. It indicates low liquidity.

Some analysts calculate working capital as simply Receivables + Inventory – Payables (which you’ll see below), ignoring everything else.

In this case, a company that is quick to collect cash from clients won’t carry a significant amount of receivables, resulting in negative working capital (because cash is not considered).

But when you use total current assets and liabilities, even if the company has high negotiating power with customers and doesn’t extend them a lot of credit, the money collected goes to cash and cash equivalents—an item considered under current assets.

Now, if the company is quick to invest the cash into new growth opportunities that generate more positive cash flow, negative working capital is a good sign.

#2) Operating Current Assets and Liabilities

When valuing a company, you’ll want to consider operational cash flows and assets.

Any revenue the company generates that is not part of its core business activities should be treated differently. The same applies to the assets that generate that revenue.

The impact of this on Free Cash Flow to the Firm (FCFF) is mostly in the EBIT, and working capital changes.

An increase in net working capital from one year to the next represents an investment that reduces the cash available to the firm. A decrease (or a negative difference) means a cash inflow.

Therefore, working capital impacts the value of a firm by affecting its free cash flow.

Now that you understand the importance of working capital in the valuation of a company, what should you include and exclude in its calculation?

These are the main operational items.

- Accounts Receivable: Money clients owe us.

- Inventory: Raw materials and finished products waiting to be sold.

- Working Cash: Cash essential to run daily operations. You can consider it an operational current asset.

- Accounts Payable: Money we owe suppliers.

- Taxes Payable: This is typically VAT (Value-Added Tax), which varies according to sales and costs. You can ignore this if it’s not significant in the company you’re valuing or if a different sales tax regimen is used in its country.

You may the wondering if does working capital include cash:

Why Is Cash Part of Working Capital?

You should include cash—but not all of it. Only the cash needed to run the firm on a day-to-day basis (working cash).

This means excluding excess cash, which is cash the company doesn’t need in order to run the business, and can invest at a market rate instead.

In other words, while you can consider a minimum amount of cash as a working capital item, you must eliminate treasury bills and long-term deposits from the WC calculation.

When computing the Enterprise Value later, you deduct this excess cash from financial debt instead.

Makes sense, right?

Let’s go through a quick example to put these concepts in motion:

Example: Is Cash Working Capital

Imagine a company with the following balance sheet items:

| Accounts receivable | 10 |

| Inventory | 5 |

| Cash and cash equivalents | 8 |

| Other current assets | 1 |

| Total Current Assets | 24 |

| Accounts payable | 9 |

| Short-term debt | 6 |

| Lease liabilities | 3 |

| VAT Payable | 2 |

| Total Current Liabilities | 20 |

The company has revenues of 100.

Regarding the cash and cash equivalents balance, it includes cash in a bank account and marketable securities such as treasury bills. As to other current assets, it is mostly derivative financial instruments.

Assuming working cash is 2% of revenues, or 100×0.02=2, the remaining cash balance of 8-2=6 is excess cash.

To assess the short-term financial health of the company, you can calculate working capital using the total values:

Since WC is positive, the company is able to cover its immediate obligations.

Now, if you’re calculating WC for the purpose of computing the FCFF and valuing a company, you include operational items only:

For the FCFF and financial modeling, whether the working capital is positive or negative doesn’t matter as much.

What matters is the variation year-to-year.

Thus, you need the same calculation for the previous year to assess if there’s an outflow of cash (positive variation) or cash inflow (negative variation).

The Bottom Line (FAQs)

Is cash included in net working capital calculation?

Working capital includes cash and all current assets if you’re valuing the companies financial health in the short-term. In this case, working capital is simply the difference between total current assets and total current liabilities. However, if you’re valuing a company and want to estimate FCFF, do not include excess cash in the working capital changes.

Why is cash not included in net working capital?

Cash is excluded from working capital only if it is excess cash—money beyond what the company needs to function properly in the course of its daily operations.

great explanation! short and effective….