When a company goes public, its existing shareholders will see their shares lose controlling power in the company. However, this equity dilution only happens when the company issues new shares to raise capital. If the shares sold to the public are done so by existing shareholders, only those shareholders will feel the difference after the IPO. Additionally, founders can maintain their voting power despite economic dilution by creating different share classes.

That’s the gist of it.

Still confused? Keep reading:

What is an IPO

An IPO (or Initial Public Offering) is when a company decides to sell shares of its stock to the public for the first time. This means anyone can buy a piece of the company and become a shareholder.

Before an IPO, the firm is usually privately owned by its founders, employees, and early investors. The goal of this post is to understand what happens to these shareholders.

By going public through a traditional IPO, the company can raise money from a large number of investors and use it to grow its business. In alternative, it can provide liquidity to its existing investors. This is the difference between a primary and secondary IPO that you’ll learn more about below.

To prepare for an IPO, the company typically hires an investment bank to help it determine the value of its shares and market them to potential investors. Once the shares are placed, they start trading on a stock exchange like the New York Stock Exchange or NASDAQ.

IPO investors hope the value of those shares will increase over time as the company expands and makes more money.

However, investing in an initial public offering can be risky because there’s no guarantee the value of the shares will go up, or that the company will be successful in the long run.

To understand what happens to existing shareholders when a company goes public, you need to know the two types of IPO:

Types of IPOs

There are two types of IPO:

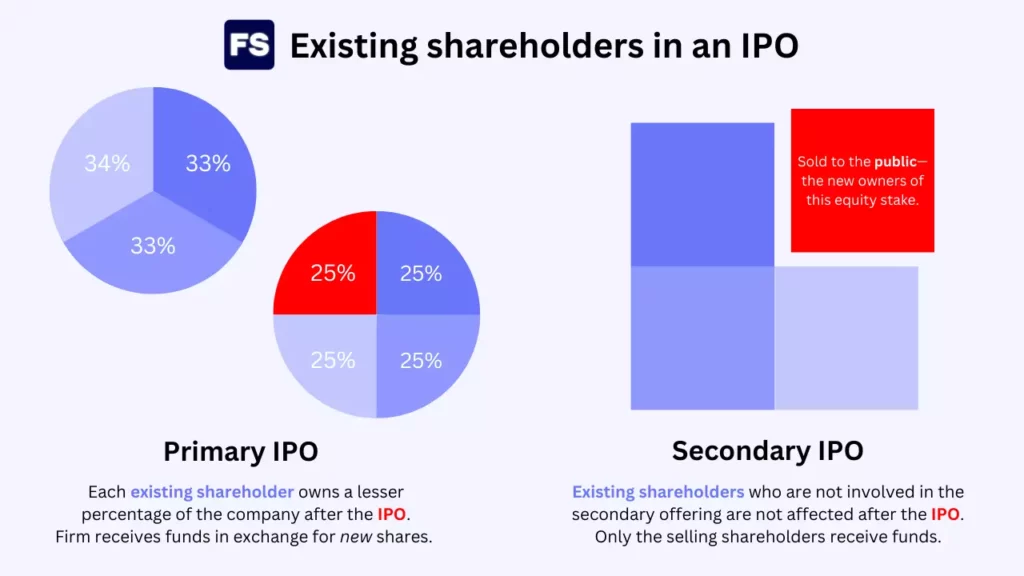

- In a primary IPO, the firm issues new shares and receives the proceeds from the issue. The firm prefers this when its goal is to fund a new investment opportunity.

- In a secondary IPO, existing shareholders sell their existing shares and receive the funds. The proceeds for the firm are zero because now new shares are issued. The firm does this type of IPO when it wants to provide liquidity to its shareholders.

Most IPOs have a mix of both primary and secondary shares.

Also, most IPOs have a lock-up period of 90 or 180 days in which company insiders, including employees, are restricted from selling shares.

A company can go public in other ways, such as through a SPAC or a direct listing, but those are beyond the scope of this post.

Hopefully, by now you start to get a picture of what happens to existing shareholders in an IPO. Let’s clarify it:

In an initial public offering, existing shareholders, such as founders, employees, and early investors, have different options and corresponding outcomes depending on:

- The specific circumstances of the issue and the type of IPO.

- Their intentions.

In a primary IPO, the ownership of an existing investor decreases. Why?

Because the issue of new shares increases the total number of shares—meaning each singular share controls less of the company. In other words, ownership control is diluted.

In the case of a secondary IPO, it depends on if the shareholder decides to participate or not in the issue.

If they do, they get an hefty payday. It’s a chance to capitalize on their investment in the firm. If not, nothing happens to their control stake. The value of their shares however? That will be affected by how much the selling shareholders agree to trade their stakes for.

Now, two things worth mentioning:

- Preferred vs. Common Stock: These are not affected the same way in an IPO. Preferred stockholders may have negotiated specific rights—such as liquidation preference and more voting power—that protect their investment, while common stockholders’ ownership and voting rights may change as a result of the offering.

- Voting rights: Founders can create different classes of shares before the IPO to preserve their control over the company. This is called a dual-class share structure, and is a decision negotiated between private investors and the board of directors. In this case, founders hold Class B shares, which have multiple votes per share, while the Class A shares the public investors hold have fewer or even no voting rights. By creating this dual-class structure, they keep voting control even after selling a portion of their ownership to the public through the IPO. In other words, their economic ownership is diluted, but they protect their vision and decision-making authority.

Let’s go through an example to put these concepts in motion:

Imagine a company with 10,000,000 shares and that is considering an IPO.

The founder has 3M shares that represent 30% ownership in the company. The co-founder has 10% of the company.

The following investors own the other 60%:

- A business angel who invested early on. She has 20% of the company.

- Two private equity firms with 1.5M shares (15%) each. They invested in the company’s series A funding round.

- Employee equity pool for future employees which accounts for 10% of the company’s shares, or 1M shares.

They have two options:

- They could issue 3,500,000 new shares and sell them to the public market in a primary transaction.

- Or, one of the private equity firms and the co-founder are interested in cashing out. Hence, the company could offer the market those shares instead.

Which one should the company choose, knowing its goal is to grow its operations? What’s the impact of this issue on existing shareholders?

Since their main goal (for now) is to develop their business and fund new projects—as opposed to providing liquidity to shareholders—they take the primary IPO. Why?

Because as we’ve seen above, when the company issues new shares it receives the funds from the sale, and can use them to fuel growth. When it sells the shares of its existing shareholders, the shareholders receive the funds from the sale.

And you know what happens to existing shareholders when new shares are issued?

Share dilution for all existing investors. Here’s a breakdown:

Total shares outstanding rise to 10M+3.5M=13.5M after the issue. This means:

- The founder went from owning 30% of the company to 3M/13.5M=22%.

- The co-founder’s 1M shares now represent around 1M/13.5M=8% of the company, as opposed to 10%. The same applies to the employees’ equity pool.

- Both private equity firms saw the ownership stake (that their 1.5M shares represent) drop from 15% to 1.5M/13.5M=11%.

- The new element in the ownership structure is the 3.5M shares float, which represents around 26% of equity.

If they went with the secondary IPO, the only shareholders concerned would be the co-founder who wants to move on to retire early, and the private equity firm looking for liquidity.

These investors would see their equity holdings drop accordingly to how much they want to sell, and their bank accounts bulk up as a result.

FAQs (Frequently Asked Questions)

What happens in an IPO?

An initial public offering (IPO) is when a private company becomes public by selling its shares on a stock exchange for the first time. The IPO allows the company to raise equity capital from public investors, and for existing institutional investors to cash out. The issuing company usually works with an investment bank to bring its shares to the public, which requires tremendous amounts of due diligence, marketing, and regulatory requirements to guarantee a successful IPO. Once that’s done, an initial stock price is released, and the public can start trading shares when the listing in the stock market happens.

The specific treatment of preferred shares in an IPO depends on the agreement within the firm. Most times, when a company goes public, preferred shares convert to common shares immediately. Why? Because otherwise, as an investor you are discouraged from participating in the offering, as you would be structurally subordinated to the existing preferred stockholders. There may also be a redemption provision in which preferred shareholders receive a cash payment upon the IPO. Furthermore, in rare cases, preferred shareholders continue to hold their shares and enjoy the associated rights and benefits.

What happens to employees when a company goes public?

In terms of business operations, there isn’t much change. That said, being a publicly traded company brings a lot of scrutiny from the SEC, so the finance, accounting, and legal departments may see changes to their routines. Many companies offer stock options to employees as part of their compensation packages. These options may increase in value when the company IPOs. And if the company didn’t have a stock-based compensation system, as a public company it becomes easier to set up and value stock-based incentives, as well as align them with market standards. Lastly, going public raises a firm’s profile. This increased visibility may attract additional new talent, and create more career advancement opportunities for existing talent.

Hello and thank you for such a concise and readable explanation. Do you happen to have an opinion on how the probable Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac IPO’s might play out? From your article, one starting point would be whether or not the US government (as I assume a major share holder) intends to cash out or not. Also, would you comment on the potential for future share value to grow after a primary IPO thereby offsetting the initial dilution. Please feel free to critique my rationale as I am an amateur investor.